A very common question people ask is: “Can I build muscle with calisthenics?” The short answer is yes but there are many nuances to it. Before you read on it might be worthwhile to check our tips for starting out with calisthenics.

It’s important to point out that beginners will see much more rapid progress in the first few months compared to athletes coming from a gym background. It is simply because the body is not accustomed to the type of resistance bodyweight exercises provide so it will adapt faster to the new “shock” to the system. In this case, a full-body routine and hitting the same muscles twice a week could be a great way to stimulate visible muscle growth.

On the other hand, if you are an experienced athlete and have been training with weights multiple times a week when switching to calisthenics you will need to be more conscious about planning your routine. In this case, more targeted split training (push/pull/legs) might be more efficient. Also, consider training each set to failure and implementing longer rest times not just in between sets but also in between workouts.

Targeting the growth of leg muscles is notoriously challenging with calisthenics. Stimulating the glutes, hamstrings, and calves without adding weight is very difficult because the legs are already used to bearing the load of our body weight during normal, daily activities. To increase the difficulty here, the implementation of unilateral and plyometric exercises makes a lot of sense. In addition, there is no harm in adding a weight vest or even a barbell with plates to our repertoire of workout equipment.

In this article you will learn what the process of muscle growth is like and how to adapt your training routine to best target hypertrophy.

How to structure your workouts for optimal hypertrophy

When it comes to building muscle with calisthenics, it’s easy to think that more is always better. We assume that cranking out as many reps and sets as possible will get us to our goals faster. But Dr. Layne Norton, a leading figure in strength and hypertrophy research, suggests a different approach. In this lengthy interview, he emphasizes the importance of what he calls “hard sets”—these are sets that push us close to failure and are truly challenging. From Dr. Norton’s perspective, the goal is quality over quantity. Let’s break down some of his key points and explore how we can use them in a bodyweight workout routine.

What’s Junk Volume?

Junk volume is when we add more sets without focusing on how hard each set actually is. For calisthenics athletes, that might mean doing endless push-ups or squats without getting close to failure. Just because we’re doing a lot of reps doesn’t mean we’re stimulating muscle growth effectively. Instead of simply piling on the volume, we should focus on sets that genuinely challenge our muscles and bring us close to fatigue. Think of each set as an opportunity to push yourself to the point where you can only do a few more reps if you had to. It’s about giving each set your full attention and making it count.

Training Close to Failure, Not at Failure Every Time

While training to failure—where you absolutely cannot complete another rep—can be helpful to understand your limits, it’s not something you need to do every time. Consistently going to failure can be too fatiguing and impact your recovery for the next workout. Dr. Norton suggests stopping within 1-3 reps of failure most of the time. For example, if you’re doing pull-ups, aim for a level where you could possibly manage one or two more if you had to, but stop there. This approach allows you to get the muscle-building benefits of training close to failure without overloading your nervous system.

Training Volume: Optimal sets and reps per workout

Volume refers to the amount of work you do in a given time period, most typically we measure it by the total number of sets and repetitions in one or more workouts.

Volume and intensity go hand in hand and can affect whether the adaptation results in increased muscle mass, strength or endurance.

Research shows that around 6-8 hard sets per muscle group in a workout is a solid starting point for hypertrophy. If you take shorter rest periods, you might be able to increase that to 8-12 sets. For a calisthenics athlete, this might mean doing 6-8 challenging sets of push-up variations for your chest or pistol squats for your legs. Quality matters here, so rather than cranking out a high volume of exercises, stick to 6-8 sets that are intense enough to make a difference. This range strikes a balance between challenging your muscles enough to grow and not overdoing it, allowing you to train more consistently.

Higher load and lower number of repetitions (1-5) coupled with longer rest times (3-5 mins) trigger a high level of neural adaptation by recruiting fast-twitch muscle fibers. This type of workout is mainly beneficial for strength development while also contributing to hypertrophy.

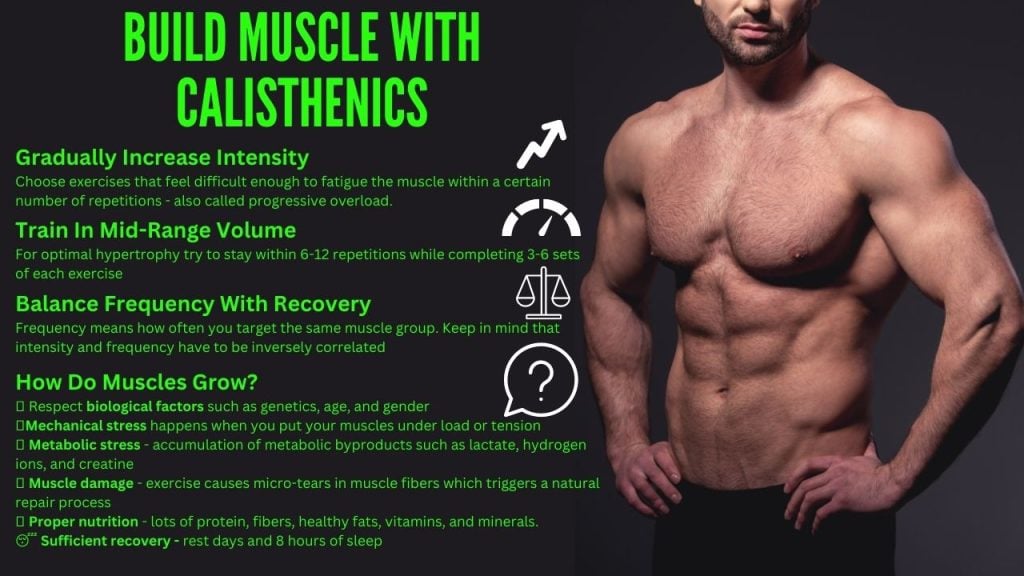

Higher volume is generally better for muscle growth than low volume. There is no agreement however in the scientific community as to what is the “ideal volume” for hypertrophy. The safe bet is to exercise within a moderate rep, set, and load range. For optimal hypertrophy try to stay within 6-12 repetitions while completing 3-6 sets of each exercise. Choose the exercises from the calisthenics progression chart that you can perform in a good form and in a way that fatigue doesn’t set in outside of the recommended rep and set ranges.

There is also proof that it’s possible to build muscle with moderately difficult exercises performed over more than 12 repetitions per set – the key here is to go with a moderate volume and perform each set to fatigue.

Training Frequency: Twice a Week per Muscle Group

Training a muscle group twice a week has been shown to be more effective than just once. So, if you’re training at home or on the go, try to hit each muscle group twice a week for the best results. For example, you could have an upper body session twice a week and a lower body session twice a week. Distributing your volume throughout the week helps manage fatigue, and you can fit more high-quality sets in without feeling too exhausted in any single session.

Volume Cycling

Dr. Norton also mentions “volume cycling,” which is a way to focus on specific muscle groups for a period of time while maintaining others. For example, you could spend 12-20 weeks focusing on your legs, with the goal of building more size or strength, while keeping your upper body in maintenance mode. By cycling your focus this way, you get targeted growth without overwhelming your whole body or burning out.

Start Low and Increase Volume Gradually

One of Dr. Norton’s main principles is to avoid jumping in with high volume right away. Instead, start with a lower volume and increase as your body adapts. If you begin with 4-5 hard sets per muscle group and feel like you’re recovering well, you can increase the number over time. This approach helps you avoid unnecessary fatigue and burnout, keeping your progress steady and sustainable.

Gradually increase intensity

In order to trigger muscle adaptation we need to challenge our muscles with sufficient intensity. This means doing exercises that feel difficult enough to fatigue the muscle within a certain number of repetitions.

Progressive mechanical tension overload or progressive overload for short is one of the major ingredients of muscle growth and architecture. This is achieved by gradually increasing the intensity of the workouts. In calisthenics, you can do it by choosing a more difficult version of the exercises on the progression chart or by adding weight.

Balance frequency with recovery

To maximize muscle hypertrophy each muscle group has to be targeted/trained frequently enough to stimulate growth. It’s important to keep in mind that intensity and frequency have to be inversely correlated. The more often you exercise the easier your individual workouts have to be in order to recover and progress.

Extra Point: Lengthened Partials and Controlled Eccentrics for Extra Gains

Two other methods Dr. Norton highlights are lengthened partials and controlled eccentrics, both of which can work wonders for calisthenics athletes.

• Lengthened Partials: Once you’re too fatigued to complete a full range of motion, try performing partial reps in the lengthened position. For instance, if you can’t do another full pistol squat, continue with partial reps in the bottom half of the movement. This keeps the muscle under tension and can help stimulate additional growth even when you’re close to fatigue.

• Controlled Eccentrics: The eccentric phase, or lowering phase, produces more hypertrophy than the lifting phase (concentric) and isn’t as taxing on your nervous system. By slowing down the eccentric, like lowering yourself slowly in a pull-up, you maximize the muscle-building potential of each rep without draining your energy too quickly. It’s a great time-saver and more effective, meaning each set with controlled eccentrics is worth twice as much as those done without control. Plus, this approach can improve your recovery rate, allowing you to train more consistently.

Putting It All Together

To optimize hypertrophy as a calisthenics athlete, here’s how I’d structure a workout based on Dr. Norton’s advice:

1. Focus on Hard Sets: Aim for around 6-8 hard sets per muscle group, ensuring each set challenges you.

2. Train Close to Failure: Keep most sets within 1-3 reps of failure to push your limits without overdoing it.

3. Hit Muscles Twice a Week: Plan your schedule so each muscle group gets trained twice weekly.

4. Experiment with Volume Cycling: Consider focusing on one muscle group for targeted growth while maintaining others.

5. Use Lengthened Partials: When you’re fatigued, perform partial reps in the lengthened position to keep muscles under tension.

6. Slow Down the Eccentric Phase: Control the lowering part of the movement to get more out of each set and promote faster recovery.

This approach is not only practical but also sustainable. By focusing on quality, managing fatigue, and using techniques like lengthened partials and controlled eccentrics, you’re setting yourself up for steady muscle growth without burning out. So, the next time you’re planning your bodyweight routine, remember that more isn’t always better—hard, focused sets can lead to bigger gains and better results in the long run.

Understanding muscle growth

The muscle tissue is made of muscle fibers and each fiber contains a single cell. Muscles grow as a result of the increase in the size of the cells they are made of. This is a form of hypertrophy.

Hypertrophy is not only related to muscle growth though. Some non-fitness-related examples are an enlarged heart due to high blood pressure or a larger liver in response to chronic alcohol consumption.

While you can induce hypertrophy in skeletal muscle with resistance training, for optimal progress there are other conditions that need to be fulfilled.

Many factors are within our control but there are some that we can’t influence. While we can optimize the way we train, eat and recover, we can’t alter our genetic code. Just like in life, we have to focus on what we can change and make the most out of what we have.

Factors contributing to muscle growth include genetics, gender, age, mechanical stress, muscle damage, metabolic stress, nutrition and recovery. Let’s address them one-by-one.

Biological factors

Genetics and gender both play a significant role in muscle hypertrophy. Studies show that DNA has about a 50% impact on the variance in lean body mass and muscle fiber proportion. We all know from experience that some people develop certain muscles much easier than others and it’s important to understand that to a significant degree, our strengths and weaknesses are hereditary.

When it comes to gender, testosterone is the deciding factor for muscle growth. Males typically experience more hypertrophy than females due to higher levels of testosterone, particularly during puberty. On average, males have about 60% more muscle mass than females.

Age is also a factor that influences the rate at which we can develop and retain muscle. Younger athletes, usually below 30, have an easier time building muscle because of the higher levels of anabolic hormones in their bodies, such as testosterone. With age, there is gradual muscle atrophy or loss of muscle mass. This happens due to decreased physical activity and subsequent decreases in hormone levels. It is important to keep in mind that with targeted nutrition and an appropriate workout plan, it is possible to build muscle and strength even in old age.

The Three Main Body Types

The concept of body types that predetermine weight gain or weight loss tendencies is often referred to as somatotypes. The three main somatotypes proposed by American psychologist William H. Sheldon are ectomorph, mesomorph, and endomorph. It's important to note that somatotypes are a generalized framework and do not provide an absolute prediction of an individual's ability to gain or lose weight. Here's a brief description of each somatotype:

- Ectomorph: Ectomorphs are generally characterized as having a lean and slender physique. They tend to have a fast metabolism and may find it challenging to gain weight, including muscle mass. Ectomorphs often have a smaller bone structure, narrower frame, and lower body fat levels.

- Mesomorph: Mesomorphs are typically considered to have a more athletic and muscular build. They have a moderate metabolism and can both gain and lose weight relatively easily. Mesomorphs tend to have a more muscular and well-defined body, with broader shoulders and a narrower waist.

- Endomorph: Endomorphs generally have a larger, rounder, and softer body type. They typically have a slower metabolism and may have a tendency to gain weight more easily, particularly in the form of body fat. Endomorphs often have a wider bone structure, more body fat, and find it more challenging to lose weight.

Mechanical stress

Mechanical stress happens when you put your muscles under load or tension. It is probably the most important driver behind muscle growth. In order to induce optimal adaptation it’s also important to gradually increase the load or time under tension. In resistance training this is called progressive overload and refers to gradually increasing the demands placed on the muscle over time.

In calisthenics, you can increase load or intensity by adjusting the body position or adding weight to the exercise while at the same time performing it in a good form through a full range of motion.

Muscle damage

Resistance training causes micro-tears in muscle fibers which triggers a natural repair process. Part of this repair response is inflammation which helps to clear the damaged tissue and trigger the recruitment of specialized satellite cells that fuse to existing muscle fibers. In other words, the body overcompensates by replacing the damaged tissue and adding more to reduce the chance of damage in the future. Muscular adaptation and growth occur as a result of this repeated muscle damage and repair cycle.

Metabolic stress

During exercise there is an accumulation of metabolic byproducts such as lactate, hydrogen ions, and creatine. There is a theory that metabolic stress stimulates the release of insulin-like growth factors and increases the production of reactive oxygen species, this way supporting the repair and growth of the muscle.

Metabolic stress can also cause muscle swelling or cell volumization which activates the pathways involved in muscle growth. The swelling can also cause stretching of the muscle membrane which may also promote growth.

Metabolic stress also stimulates the production of heat proteins which aid in protecting the muscle from damage.

Proper nutrition

A sufficient amount of protein is necessary to support muscle growth and repair. It is generally recommended that athletes consume 1.5-2.0 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day, depending on their fitness level and goals. Some studies found that consuming more than 30g of protein in a single meal did not significantly enhance muscle protein synthesis. Therefore it might be better to distribute the required protein intake into more, smaller meals per day e.g. for a 90kg person 6 meals containing 30g of protein each.

Consuming carbohydrates before and after exercise can also help to support muscle glycogen stores and enhance recovery. Additionally, athletes should aim to consume an adequate amount of healthy fats, vitamins, and minerals.

What happens if I exercise properly but don’t eat enough protein?

To repair and rebuild the muscle after resistance training the body uses amino acids that are the building blocks of protein and are necessary for protein synthesis. If you don’t consume enough protein, your body won’t be able to rebuild the muscle tissue effectively. Low protein intake at increased physical activity levels may also increase the recovery time needed and weaken the immune system.

Sufficient recovery

Adequate rest time between workouts is crucial for muscle growth and injury prevention.

During sleep, the body repairs and rebuilds the muscle tissue that has been damaged during exercise. The release of growth hormones during sleep promotes protein synthesis which is an important prerequisite for muscle growth.

Sleep and rest also help with cortisol regulation. Cortisol is a hormone that is released in response to stress such as exercise. High levels of cortisol can have an adverse catabolic effect on muscle growth as they break down muscle tissue.

One of the most common follow-up questions I get after explaining how to build muscle with calisthenics is whether you can keep progressing just by doing more work instead of harder exercises. That’s exactly what I break down in my dedicated article on high-volume training for muscle growth, where I explain which muscle groups respond best to added reps and sets, where volume starts to fail, and how to use it intelligently without stalling your progress.